In a long friendship, Gretchen Albrecht and Catharina van Bohemen have discussed art, books, poetry, and aspects of the Roman Catholic tradition. Here, Catharina examines the genesis and development of Albrecht’s hemispheres.

Gretchen Albrecht is a luminous presence in the art of Aotearoa. She is known especially for her “hemispheres” (she has sometimes called them lunettes), semi-circular canvases which eschew the traditional rectangle. Her broad concentric sweeps of colour speak to the physical act of painting and ask us to contemplate the hemisphere form itself.

She has also frequently worked in series – paintings that “talk” to art, poetry, and religious experience within the western tradition and allude to her own life experiences. Two sequences examine the life of Mary, the mother of God. The first, Colloquy, is five paintings considering the Annunciation – when the Angel appeared to Mary; the second, Seven Sorrows of Mary, reflects the anguish she experienced as her child suffered, died, and was buried. Seasonal is a quartet responding to the art of poetry with references to Ovid, medieval poetry, and Keats.

In April, Albrecht’s largest series, Eight Hours will open at Two Rooms Gallery in Auckland. For this series she has harnessed her work to the eight Canonical hours of the Divine Office, prayers of praise in the Roman Catholic monastic tradition which are still sung at intervals throughout night and day in plainchant.

Her long (more than 50 years) career has been prolific and the hemispheres typify her distinctive output: fluid stains and floods and squeegeed sweeps of colour, contained and organised by various geometric devices and especially shaped canvases.

Albrecht’s Eight Hours are her response to the Hours, and titled after them. Like them, the paintings begin and end in the dark with Vigils (prayers traditionally sung at about 2 am), and Compline, the eighth hour. Vigils is a stately march of black wings soaring towards and subsuming an inky expanse, and in Compline darkness drops over a velvet sky still suffused with starlight.

Albrecht’s Hours are lustrous responses to the day, to light and the passing of time. There is in these works a rhythmic quality; her colours, her contrasts of light and mysterious shadowing, call and respond to one another, not unlike the antiphonal chant of plainsong in monastic oratories.

She painted the Hours over the past four years, but their genesis came after she visited monasteries in France in the 1980s, where the consideration of a life of prayer plaited with work affected her deeply. “The Hours” says Albrecht, “celebrate the day, the seasons, the year. The hours of day into night are something everyone experiences – we all live them. Their religious underpinning provides a perfect way for me to gather in metaphor, and the physical and emotional experience of being a painter here.”

For fifty years Albrecht has celebrated living in Aotearoa and has called herself an abstract landscape painter: ii but this definition takes in a lifelong conversation with Western poetry and art which, until 1979 when she went overseas, she had studied only in books.

Francesca’s Madonna del Parto. “Confronted with this astonishing great female image, I responded with an intensity of personal experience. It led two years later to the first of my hemisphere paintings, and that experience remains a watershed moment to this day.”

Albrecht says she was moved not just by Mary’s unflinching gaze, one protective hand on her dress, splitting over the bulge of the growing child, but also how the painting fits intimately within the curve of the chapel’s architecture, making the image visible through the fabric of the architecture. “A perfect containment for revelation.”

This revelation brought forth Pacific Annunciation (1984), the precursor of the five Colloquy paintings. It explores the encounter between Mary and the angel Gabriel in terms of feelings Mary might have experienced when the angel appeared, according to 15th century Franciscan Friar and preacher Roberto Caracciolo: disquiet, reflection, interrogation, submission, and merit.

Albrecht’s paint strokes, in an almost black-red, are agitated in the Mary quadrant of Disquiet. The contrasts between the quadrants, the colour and brushwork are manipulated to evoke successive emotional states to end with the golden radiance of Merit, the final painting, intimating Mary’s acceptance that she is to be the mother of God.

Pacific Annunciation is a deliberate title, not only for the resonance of the word pacific – Albrecht wanted to represent transcendent experience as universal whether it might happen in Israel, Florence, or the southern hemisphere. As a mother of a son, she reacted viscerally to these depictions of impending motherhood; as an artist she used the hemisphere to echo Piero’s painting held within the chapel’s architecture, giving her what she described as “a shape to contain the feeling.”

Pacific Annunciation, like many of the hemispheres, consists of two canvas-covered quadrants bolted together. The shimmering pink of the left quadrant, she said, reflects the shimmering speed of the angel’s wings; the deep blue of the right Mary’s quiet acceptance (and the blue depth of the Pacific). The quadrants are equal and separate. At their junction, pink paint becomes lighter: she explains this as a “conception point” vi where two forms become a third . The curve of the hemisphere may also suggest the curve of a pregnant woman’s belly.

As Albrecht made the hemisphere her shape, she explored the possibilities of edges – how paint could furl and dance towards and away from them; how bolted edges invoke separation or, perhaps reconciliation; how a “conception point” can develop into a geyser-like painted shape.

This treatment of the boundary between bolted quadrants may be seen in her powerful Seasonal of 1985 – four large hemispheres with titles Blossom, Arbour, Orchard (for Keats), and Exile, that allude to the poets’ symbolic use of the seasons. Albrecht loves poetry. Her titles often refer to words or phrases she’s read and remembered, and can guide us to a more nuanced response to her work. The Southern Alps at sunset stimulated Exile, the winter painting, and a fragment of poetry by the exiled Ovid. But the funnels of indigo exploding separately from the base of the painting also recall the medieval poets for whom winter represented exile from Eden, from grace. The intrusion of darkness and cold into paradise.

Eight Hours is Albrecht’s largest sequence responding to a religious or literary tradition. In the 1990s she experimented with her other distinctive shape – the oval. She sought a form that would allow her to “talk about things that took off, that didn’t have that gravity – that baseline – and that floated.” The oval, with its egg-like shape and root in the Latin ovum, represented for her a more malleable (feminine) and fluid shape – than a circular painting

or tondo.

She also revisited the life of Mary with her 1995 series Seven Sorrows of Mary, those foretold by Simeon at the presentation of the child Jesus in the Temple. These sombre ovals echo the black beads of the Seven Sorrows Rosary and like her hemispheres, they are stained canvases overlaid with swirls of inky black paint. Mary’s love for her son is pierced with pain; Albrecht’s “nomadic geometries” (a phrase borrowed from poet Octavio Paz), monumental rectangles of red, white, purple, and gold oil paint, travel over the paint recording the depth and passage of her grief.

With Eight Hours, says Albrecht, hemispheres have “rocketed back into my life.” They are her largest sequence and a triumphant celebration of nearly sixty years of making art since her first solo exhibtion in 1964 at the Ikon Gallery in Auckland.

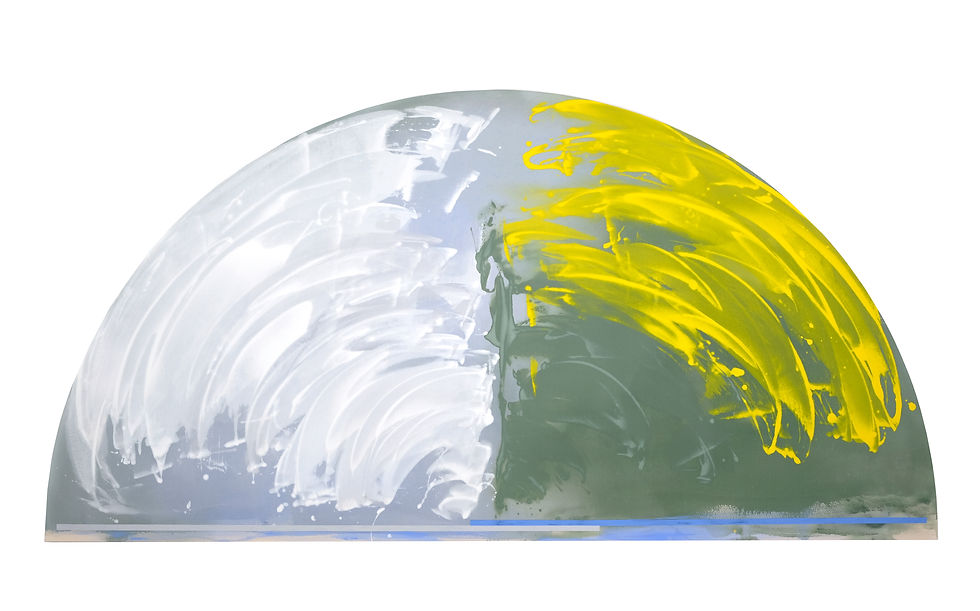

Unlike most of her earlier hemispheres these are undivided, so that paint can travel uninterrupted over the entire surface. It pours or pauses: in Terce – the Third Hour, for example, it retreats at the top of the hemisphere to reveal a misty expansiveness.

In her bolted canvases, the join often signifies conversation: sides talking to each other within the hemisphere. In Eight Hours, however, “it’s the hours talking to one another” hence the privilege of seeing the series together so their painterly music is experienced antiphonally.

Eight Hours recall the Seven Sorrows, in again using nomadic geometries. In Seven Sorrows, however, these geometries were solid stencilled rectangles and alluded to character, event, emotion and artistic balance; in Eight Hours, they are slender whispers of colour anchoring and echoing the arcs of paint above them. Eight Hours are related to Seasonal in the sense that they are grounded in and celebrate the natural world. But their sacred ritual scaffold transforms everyday existence into a contemplation of the ineffable.

First published in Art Zone #90

Comments