A group of men convene in the desert at an oblong table with a pink tablecloth. They sit side on or backs to us, in conversation but static. The shape is so dense it could be a hunk of cake, the figures bean-like and stark white. Sophie McKinnon reviews Rose Wylie's London exhibition, Quack Quack.

Rose Wylie: Quack Quack

Serpentine Sackler Gallery, London

30 November – 11 February 2018

Panels of flat sand meet them from above and below, and trees like stick men grow down from the horizon line. Curling painted letters say, among other things, 'Privatization Corruption Deregulation Dir Stephen Gaghan George Clooney Matt Damon'. This is poster notation for the film Syriana, but they are not descriptors of what we are looking at. The scene is a cinematic moment remembered, complete with textual elements and like much of Wylie's work, should be observed first, and read second. The paintings in Quack Quack, the artist’s first institutional show in London, are full of words. They spill through the pieces like alphabet soup. It’s hard not to focus on them and search for narrative, but Wylie seems to hope we will trust a different set of instincts. We should be absorbing the whole assemblage of images and words, at once deliberate and arbitrary because filtered through memory.

Wylie’s passing references to recognisable matter and media – film culture, celebrity, news announcements, football matches – help viewers to navigate the new place she takes them to. She keeps numerous notebooks, jotting down observations, conversations, critiques, locations, and reflections. This process of immediate response is clearly vital to her work, which reads like stream-of-consciousness portals into various situations. We are left with clues, letters rendered unselfconsciously in robust brush strokes. The canvases, enormous and unprimed, bear down on you with apparent purpose. They are almost all equal in size, reflecting the dimensions of her studio wall in Kent. Hung closely, or wrapping around the gallery like a story board, they read together like a huge puzzle.

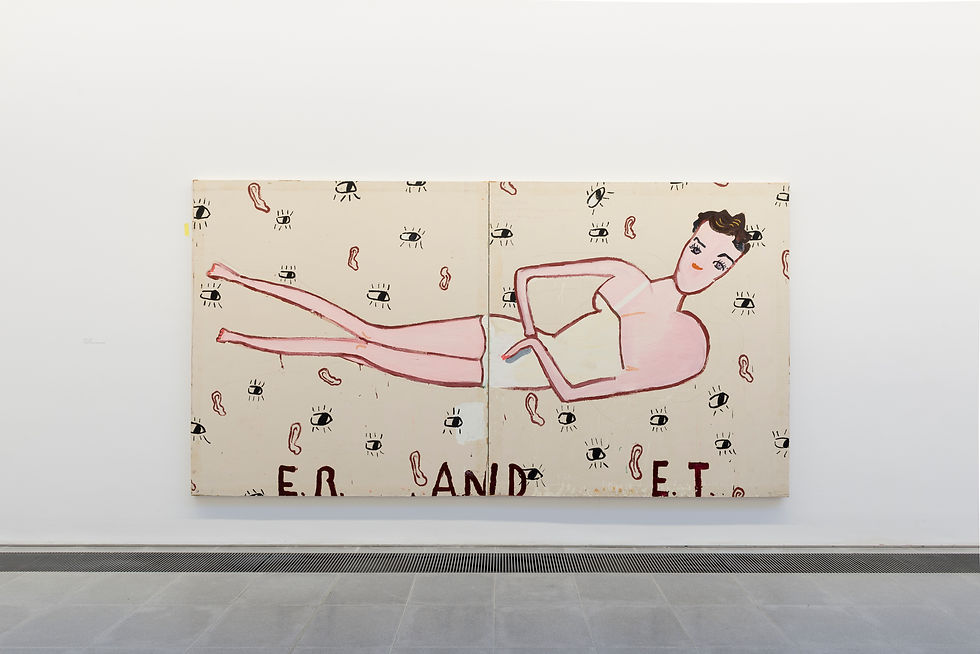

An ER & ET (Elizabeth Regina and Elizabeth Taylor) odalisque floats on a sea of painted eyes and ears, gazing at you.

Park Duck (2017) presents picture-book dogs strolling an imagined landscape complete with pyramids, a plane-sized and muddied mallard in profile beneath them. Black, thickly painted bomber planes circle above a pond in Kensington Park, where the Serpentine Gallery is situated, and where Wylie recalls feeding ducks amidst warnings of World War II air raids and the 'ack ack' sounds of anti-aircraft fire. On another wall, a parade-like frieze shows Nicole Kidman in her red-carpet gown with thin black straps, moving in and out of the letters of the words ‘black strap’, obscuring them to read 'quack quack' or even 'ack ack'. It’s easy to process Wylie’s paintings as simplistic explorations of shape, size, colour, and youthful schematics. But compositionally, they are masterful: explicit in certain details and assemblages while remaining gestural and open. They resurrect histories with childhood visions of reality, but without a lick of sentimentally. Busy and exuberant, each piece is blocked out with urgent figures that lean, skip, march, dine, or look out at you as if to ask why you have just happened upon the world they are inhabiting.

In more than one interview Rose Wylie has mentioned that she would rather not be known for her age. Understandably, anyone whose body of work covers a world war and six decades has much more to talk about. What is extraordinary about her paintings however, is their immediacy and freshness – not just in style, but in content, candour, and character. Pieces made in 1990s could have been made in the past five years, with some resemblance to work by younger artists, such as Laura Owens for example, whose playful, loose work we have readily embraced. Before reading the biographical wall text in the Serpentine, I felt certain that Wylie was a young artist, in her late twenties or early thirties. A colleague back in New York had assumed the same and we were amazed to learn she is 84. Why should this matter? It doesn’t. But it reflects an interesting recent trend, of the older female artist presented as if new and recently discovered. Carmen Herrera’s solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2016 was her first in 32 years, and she was 101 years old when it opened. Helen Pashgian, a pioneer of the California Light and Space movement in the 1960s, enjoyed a major retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2014, when she was 80. Howardena Pindell, at 74, is named on the cover of ArtForum February 2018. Carolee Schneemann’s current retrospective at MoMA PS1 in New York is the first in her career, despite her being active (and influential) since the late 1950s.

The gender discrimination that meant these women were institutionally underrepresented in their era is obvious. Wylie herself bowed out of the commercial art scene to be a mother and homemaker, not returning until she was in her 40s. She won the prestigious John Moores Prize for painting when she was 80, but many leading art awards (the Turner Prize, for example) still carry an age cap. The first wall in the Serpentine exhibition is hung with a two-part portrait of a jubilant ice skater, her broad body decked in pink tulle soaring through lopsided stars, her capricious subtitle reading 'I WILL I WIN'. Wylie’s work resonates as clearly as it did the moment it was made. Her paintings communicate an acute sense of place and time, but one rooted in the specificity of memory rather than historic accuracy. Her powers of observation are enduringly sincere, and testament to an inexhaustible joy in the present, whether that be then or now.

First published ArtZone #73

Comentarios